The Founding Father of U.S. Counterintelligence

Patriot, Revolutionary & Statesman

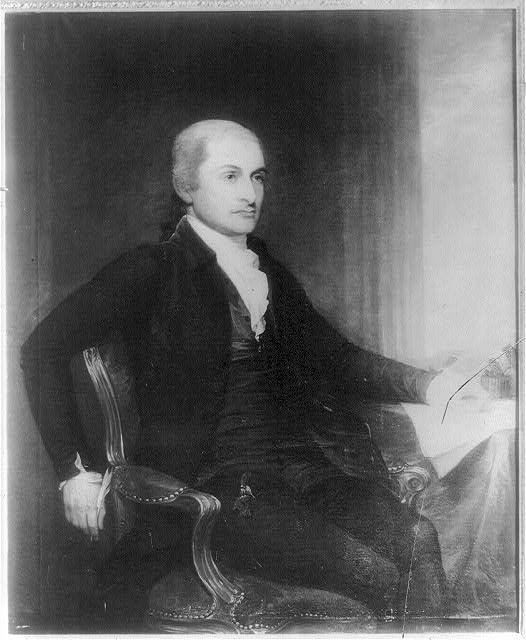

Born in New York in 1745, John Jay was one of the framers of the Constitution, author of five of The Federalist Papers, and the first Chief Justice of the United States.

A patriot devoted to public service, his achievements in virtually every branch and level of government are indeed noteworthy, both during the American Revolutionary War and following it.

During the American Revolution, John Jay played a crucial role at home as a president of the wartime Continental Congress and abroad as a representative of the new republic.

In addition to Jay’s roles as statesman and diplomat, one of the more unheralded aspects of his public service was his involvement in counterintelligence during the Revolutionary War. Indeed, he is credited as having been the founder of counterintelligence in America. He also is credited with having saved the life of George Washington.

Influence at Home & Abroad

His foreign assignments included one in Spain where, in 1780, he lobbied for diplomatic recognition for the new United States, monetary support, and a trade treaty; and then Paris in 1783 where he joined John Adams and Benjamin Franklin in negotiating the Treaty of Paris to end the Revolutionary War. The following year, he served as Secretary of Foreign Affairs (the precursor to the position of Secretary of State) under the Articles of Confederation.

American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Agreement with Great Britain, Benjamin West, 1783. The United States delegation at the Treaty of Paris included John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin. The British commissioners refused to pose, and the picture was never finished.

In 1794, while Chief Justice, Jay traveled to Great Britain in order to settle contentious issues between the two countries that remained following the war. His efforts resulted in the “Jay Treaty,” which accomplished the important goal of averting a war with Britain. In later years, Jay co-authored the New York Constitution and was responsible for enacting legislation that phased out slavery in the state of New York.

The Birth of American Counterintelligence

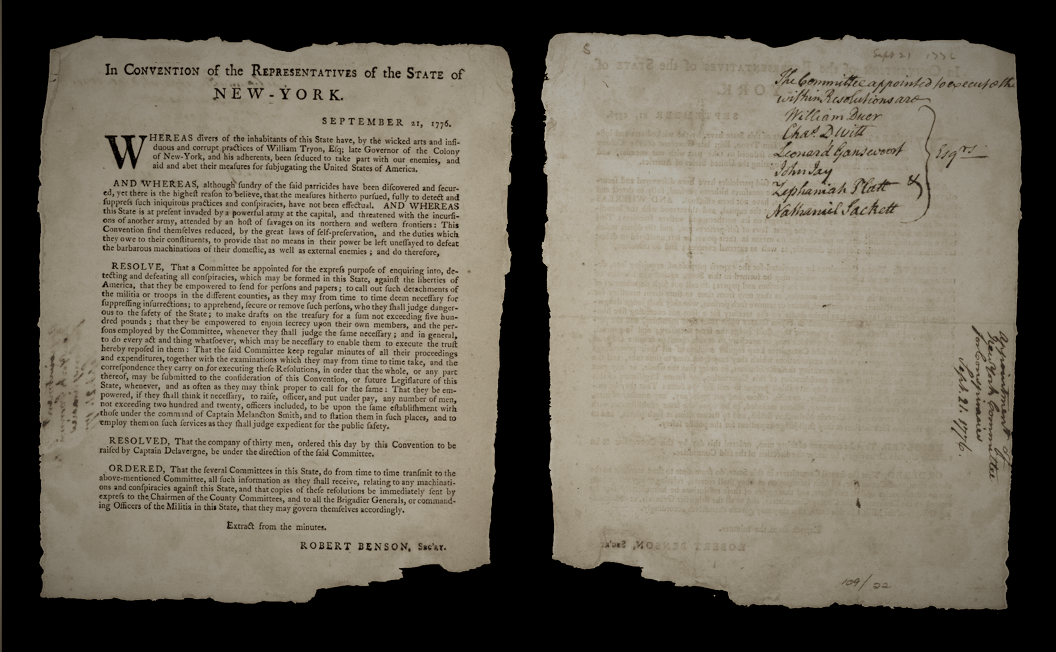

Jay’s foray into counterintelligence began in 1776 when, at the age of thirty, he headed a New York State executive body called the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies. The Committee's role, according to the resolution establishing it, was “inquiring into, detecting and defeating all conspiracies which may be formed ... against the liberties of America.”

Today, the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies is recognized as our nation’s first dedicated counterintelligence agency.

September 1776 New York state representatives resolution establishing the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies, signed by John Jay.

In essence, its charter was not only to collect intelligence on the enemy but also to conduct counterintelligence activities. The Committee was comprised of carefully selected members of New York’s Provincial Congress who were sworn to secrecy and who had a company of militia under their command to execute the committee’s charter, which included making arrests, incarcerations, and deportations. Over the course of its existence, the Committee investigated more than 500 cases involving betrayal and sedition.

The Treachery of Governor William Tryon

The September 1776 resolution that gave birth to the New York Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies specifically noted the treacherous activity of one man, William Tryon:

“Whereas divers of the inhabitants of this State have, by the wicked arts and insidious and corrupt practices of William Tryon, Esq., late Governor of the colony of New-York, and his adherents, been seduced to take part with our enemies, and aid and abet their measures for subjugating the United States of America…”

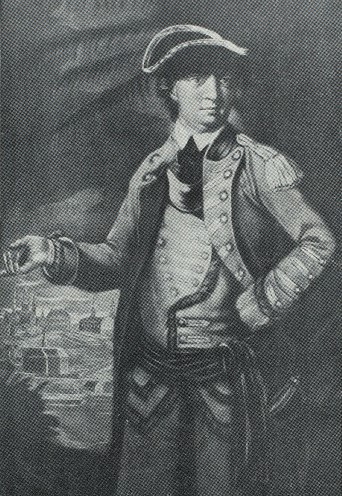

Portrait of Gov. William Tryon.

During one of the Committee’s early investigations, it learned that William Tryon, a British military officer—and governor of the British colony of New York—was running spy networks throughout the colonies, actively recruiting spies for pay. Indeed, in a letter to Continental Congress delegate Edward Rutledge in October 1776, John Jay wrote, “Governor Tryon has been very mischievous: and we find our hands full in counteracting and suppressing the conspiracies formed by him and his adherents.”

During one of the Committee’s early investigations, it learned that William Tryon, a British military officer—and governor of the British colony of New York—was running spy networks throughout the colonies, actively recruiting spies for pay. Indeed, in a letter to Continental Congress delegate Edward Rutledge in October 1776, John Jay wrote, “Governor Tryon has been very mischievous: and we find our hands full in counteracting and suppressing the conspiracies formed by him and his adherents.”

Tryon's Many Mischiefs

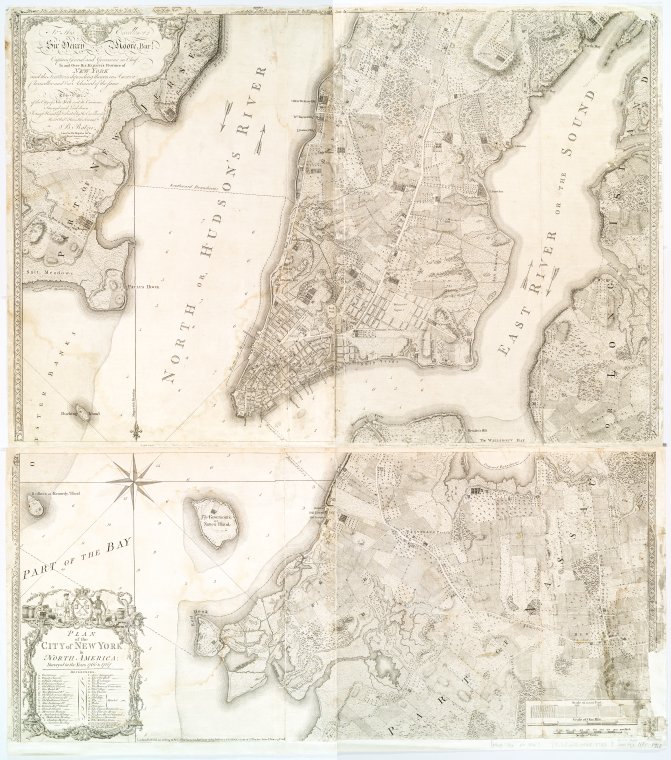

Tryon had become infamous for his brutality as governor of North Carolina from 1764 to 1771, and he was intent on leading New York with the same show of viciousness. But on June 25, 1775, following a year-long trip to London, his return to New York coincided with a parade in New York City honoring General George Washington, who had stopped there on his way from Philadelphia to Boston.

City of New York, surveyed in 1766 and 1767, NY Public Library.

Fearing for his life at the hands of colonists, Tryon sought refuge aboard the HMS Duchess of Gordon, which was docked in New York harbor alongside a 64-gun man-of-war, the HMS Asia, for protection.

Fearing for his life at the hands of colonists, Tryon sought refuge aboard the HMS Duchess of Gordon, which was docked in New York harbor alongside a 64-gun man-of-war, the HMS Asia, for protection.

From this lair, Tryon reportedly oversaw a money counterfeiting workshop and conspired with sympathizers who came to the ship regularly to meet with him. One such visitor was New York Mayor David Matthews who, together with Tryon and a number of Washington’s personal guards, hatched a treacherous plot against the General.

Tryon remained there, in self-exile, until November 1776, when New York was officially placed under British martial law.

The Battle with Benedict Arnold

Tryon would meet his match in the Battle of Ridgefield in April 1777 where Benedict Arnold, who at the time was one of Washington’s most fearless generals, would lead his troops to try to block the British advance on Connecticut. Despite having two horses shot out from under him on the battlefield, Arnold, according to a witness, “exhibited the greatest marks of bravery, coolness, and fortitude.”

War hero, turned traitor, Benedict Arnold.

Although Tryon's troops suffered twice as many casualties as did Arnold, he succeeded in achieving his tactical objective. As for Arnold, embittered by the lack of recognition and a well-deserved promotion, he would be elevated, belatedly, to the rank of major general following the pivotal Battle of Saratoga six months later.

Although Tryon's troops suffered twice as many casualties as did Arnold, he succeeded in achieving his tactical objective. As for Arnold, embittered by the lack of recognition and a well-deserved promotion, he would be elevated, belatedly, to the rank of major general following the pivotal Battle of Saratoga six months later.

Regrettably, this recognition was seen by Arnold as too little, too late, and he would eventually go from being George Washington’s most heralded fighting general to one of the most notorious spies and traitors in American history.

Foiling a Plot to Kill George Washington

In 1776, the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies under John Jay was investigating a loyalist plan for a surprise attack on the core of the Continental Army in New York City, when it uncovered a plot against General Washington. Washington, himself an able spymaster and a visionary who understood the value of intelligence, was at the time directing agent networks that used an array of espionage tradecraft, including ciphers, secret writing, and dead drops.

To Washington, intelligence collection was vital to the defense of the nation. But a number of Washington’s elite bodyguards, the “Life Guards,” had allied themselves with the British; and they plotted to capture or assassinate the General. John Jay and his Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies unraveled the plot; and one of the guards, Thomas Hickey, was executed for his involvement.

Quashing Counterfeiters & Clandestine Operations

Another act of sedition investigated by the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies was the counterfeiting of colonial currency, an undertaking aimed at weakening the colonies and bankrupting the Continental army. The potential consequences of counterfeiting were so perilous to the fledgling nation’s existence that some years later the Continental Congress would enact a law making it a crime punishable by death and would recall all its paper currency in 1780.

John Jay, Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, 1794

A Lasting Legacy

During the Revolutionary War, John Jay played a crucial intelligence role directing clandestine operatives and running counterintelligence missions.

This work directly informed the position he later took on the value of intelligence in one of the Federalist essays he authored. Jay’s Federalist No. 64 demonstrated his understanding of the government’s requirement for protection of sources and methods and argued for the right of the Executive Branch to carry out intelligence operations in secret.

Excerpt from Federalist No. 64, March 7, 1788

“It seldom happens in the negotiation of treaties, of whatever nature, but that perfect SECRECY and immediate DESPATCH are sometimes requisite. These are cases where the most useful intelligence may be obtained, if the persons possessing it can be relieved from apprehensions of discovery. Those apprehensions will operate on those persons whether they are actuated by mercenary or friendly motives; and there doubtless are many of both descriptions, who would rely on the secrecy of the President, but who would not confide in that of the Senate, and still less in that of a large popular Assembly. The convention have done well, therefore, in so disposing of the power of making treaties, that although the President must, in forming them, act by the advice and consent of the Senate, yet he will be able to manage the business of intelligence in such a manner as prudence may suggest.”The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 essays authored by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788 that expound on specific provisions of the proposed Constitution of the United States, whose adoption they were endorsing over the existing Articles of Confederation.

John Jay died in New York in 1829 at the age of 83, but his legacy lives on. His contributions to our nation, as jurist, legislator, and author are enormous, but without Jay's insightful efforts in the realm of counterintelligence, the course of our nation’s history—even our lives today—might be very different.

John Jay’s work marked the start of our nation’s counterintelligence efforts, but the story of espionage in America is only just beginning. We’ll be telling that story, from the Revolutionary War to the present day, right here on Intel.gov.

Visit The Digital Experience for a look at what’s to come and learn all about NCSC’s special Wall of Spies exhibit at Intel.gov/wall-of-spies.

More About the Wall of Spies Experience:

DIRECTOR EVANINA'S WELCOME

A LOOK INSIDE THE EXHIBIT

THE FOUNDING FATHER OF "CI"

THE DIGITAL EXPERIENCE

ABOUT NCSC

RETURN TO HOME